Following our series on Italian Westerns the next obvious genre to explore was Film Noir. If pressed I would have to say that if I had to choose a favorite cinematic idiom it would be the crime film. I generally look upon my life as a peaceful and pleasant one, free of grand emotional distress and criminal temptation, and I've no desire whatsoever for that to change. But I'm always aware of the fact that in a single instant it could. I could be in the wrong place at the wrong time and my life could turn completely upside down. It is in that spirit that I have always enjoyed the crime film. Be it the psychological thriller, the tale of the criminal underground, the private eye saga, a reflection on the weakness of the flesh or the simple case of a wrong turn, the best of these films offer a window into a life that might be.

There has been a lot of arguing back and forth as to what constitutes Film Noir since the term was retroactively coined. Billy Wilder and Otto Preminger did not set out to make "Film Noir". They simply made the films that they did and and the critics later would identify their films with the label.

When putting this series together I was aware that there would be those who might argue with my definition of Noir, suggesting that certain films would be more appropriately placed in another box. The Manchurian Candidate (A political thriller) and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane (often regarded as a horror film) are not typically offered up a prime examples of Noir, but for me they held a place of honor somewhere on the spectrum. On the other hand, as fond as I am of The Maltese Falcon, I don't recognize it as Noir. My reasoning being that in the end there really aren't any gray areas of human psychology to be found in Hammett's book. Spade is the good guy, and the rest of them are crooks, motivated principally by greed. In the same way Laura is not Noir, but instead exists in the same realm as Agatha Christie parlor mysteries. In the end the characters' motivations are pretty cut and dry. Laura might have edged towards Noir if (apologies for the spoiler) the titular character didn't turn out to be alive after all, and Dana Andrew's Detective McPherson was forced to confront his own necrophilic obsession.

What follows are the posters I made for the Night Of Noir at Mother's Velvet Lounge from April of 2007 through June of 2009, along with some of the notes I emailed to the invitees.

The Big Heat (1953) Fritz Lang

I decided to begin the Film Noir series with the The Big Heat for a variety of reasons. First is that Fritz Lang is arguable the father of Film Noir, with films like M and The Testament Of Dr. Mabuse really setting the foundation of the genre. Also this is probably Lang's best Hollywood film, which is to take nothing away from the likes of You Only Live Once and Clash By Night. Another reason is the presence of two of my favorite actors of the period; Gloria Grahame as Debbie Marsh and Lee Marvin as Vince Stone. This was early enough in Marvin's career that he was still playing the heavy, but good or bad, he was a towering icon of the very kind of film I have always loved most.

I don't recall if I wrote any pre-screening notes on this one, but if I did they seem to be gone now. I do recall that my audience was really surprised how uncompromising a film from this era could be. From Stone's brutal treatment of Debbie to the fate of Sgt. Frank Bannion's (Glenn Ford) family, this film was one seriously dark number. Yet the compassionate relationship that develops between Bannion and Debbie is a distinctly moving one in which two broken souls come together in a non-romantic way. Lang was never big on "Hollywood endings", often to his disparagement within the industry, and The Big Heat stands as a testament to his integrity as one of the greatest film makers of any era.

On May 9th, Nights Of Noir returns to Mother’s Velvet Lounge when we present Otto Preminger’s brilliant 1950 opus, Where The Sidewalk Ends, starring Dana Andrews, Gene Tierney, Gary Merrill and Karl Malden.

We are really excited to share with you this lesser known, yet pitch-perfect and exquisitely crafted work of Noir, with its powerful urban compositions by cinematographer Joseph LaShelle (Laura, The Apartment), that evoke classic pulp illustrations as vividly as any film I've seen from the period. The tight Ben Hecht script is rich with the kind of gritty moral dilemma that drives this genre.

Preminger brings back together the two leads of his 1944 hit Laura, Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney; with Andrews in the role of police Sgt. Mark Dixon, a conflicted detective whose brutality towards the suspects in his custody is the result of his shame at having a father who was himself a criminal. His tendencies get the better of him, and draw him into a world of subterfuge and deception, which he soon realizes will likely shatter the life of the woman with whom he has fallen in love (Tierney). Karl Malden makes one of his earlier appearances in the kind of role for which he would always be best remembered; that of a by-the-book detective, and the great character actor, Gary Merrill (Mr. Bette Davis) is the Machiavellian crime boss, Tom Scalise.

Out Of The Past (1947) Jacques Tourneur

On June 6th, Nights Of Noir returns to Mother’s Velvet Lounge when we present Jacques Tourneur’s classic 1947 Private Eye thriller, Out Of The Past, starring the incomparable Robert Mitchum, Jane Greer, Kirk Douglas and Rhonda Fleming.

This film is regarded by many critics (including your curator) as one of the very finest examples of detective-noir from the post-war period. A brilliant storyteller, Tourneur (Cat People, I Walked With A Zombie, The Night Of The Demon) weaves an intricate web of suspense, romance and dark destinies with a superb screenplay by Daniel Mainwaring (from his own novel, “Build My Gallows High”) and the great James M. Cain (The Postman Always Rings Twice, Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce).

Though on the surface, this film might look like a classically styled Private Eye yarn, it is significantly more sophisticated than most, with complex characters and rich plot mechanics. Whereas, the great heroes of crime fiction, such as Chandler’s Phil Marlowe or Hammett’s Sam Spade, are generally fixed characters from story to story, Jeff Bailey (Mitchum) is a character whose life is in a constant state of upheaval. Though his hard boiled manner and snappy rhetoric make him a brother to the above mentioned private dicks, his Achilles heel is much more evident. The main one comes in the form of the irresistibly alluring Kathie Moffat (Jane Greer), rebellious girlfriend of mobster Whit Sterling (Kirk Douglas), in whom she has recently planted a bullet, and then skipped off to Mexico. Still crazy in love with her, Sterling wants Kathie back, and hires Jeff to track her down. But once in Mexico…

…well, let’s not give anything away just yet.

Kiss Me Deadly (1955) Robert Aldrich

On December 5th, Nights Of Noir returns to Mother’s Velvet Lounge when we present Robert Aldrich’s classic 1955 adaptation of Mickey Spillane’s Kiss Me Deadly, starring Ralph Meeker as hard boiled private eye, Mike Hammer, with Albert Dekker, Maxine Cooper, Gabby Rodgers, and Cloris Leachman in her first feature film role.

This is perhaps the quintessential “Atom Age” detective film, which speaks to a lot of the popular fears that were held in those years, including the growing sense of a devaluation of human life. Mickey Spillane, the creator of the legendary private dick was right-wing in the extreme and an avid anti-communist, while Robert Aldrich and screen-writer Al Bezzerides conversely were more along the lines of veiled lefties (the latter was actually blacklisted in McCarthy’s assault on Hollywood) who used the former’s morality to their own ends. Spillane was outraged by the result and disowned it despite the fact that it is really the only film adaptation of his work that has survived critical judgment over the years.

Ralph Meeker plays Hammer as part bachelor pad sleaze-ball and part Neanderthal, and it’s interesting to note that he made a career of portraying tough guys and crooked cops, and was an unconventional choice for the “Hero”. But these are exactly the qualities that Aldrich uses to illustrate the brutality of the world that he inhabits. Without giving too much away, Kiss Me Deadly has some genuinely shocking moments (though not necessarily graphic ones) that seem particularly striking even in our contemporary age of ultra-violent cinema.

Angel Face (1952) Otto Preminger

On March 5th, Nights Of Noir returns to Mother’s Velvet Lounge when we present Otto Preminger’s brilliant 1952 offering, Angel Face, starring Robert Mitchum and Jean Simmons

I am no less impressed by Angel Face than I was when I first saw it 20 years ago, but find my self a little on the fence as to whether or not it really can be so easily categorized either as Film-Noir, psycho-drama or melodrama. While it possesses elements of all those genres, they all come together to create an idiom all its own. Most of the film takes place in daylight and little of it occurs within an the typical urban setting we generally associate with Noir, though the content is as dark as anything made in Hollywood in that period.

This film, despite the element of murder, is concerned with the psychological arc of its heroine, Diane Treymayne (Simmons), and at times feels like a "woman's film" in the spirit of Douglas Sirk. It’s a story that could have been written by James M. Cain (The Postman Always Rings Twice, Mildred Pierce) in that, while murder acts as the peripatetic event within the characters' lives, it is a secondary byproduct of sexual obsession. This it shares in common with John Stahl's Leave Her to Heaven which also features a manipulative anti-heroine who is driven by a paternal obsession. But whereas Gene Tierney's character in that film is the same deadly schemer at the end of the story that she was at the beginning (even in death), Diane's conscience is seriously shaken by the cost of her selfishness and experiences something of an epiphany. Unlike the traditional femme fatale, who expresses regret over her actions either to save her skin or as yet another ploy, Dianne truly regrets her actions and seeks some kind of punishment.

Conversely, Mitchum's Frank Jessup, is essentially an innocent, at least as far as the murder and complicity in Diane's games is concerned, but he is a phenomenally callous and egotistical one. In the end, he is far less sympathetic despite his innocence. This complexity of emotions and morality were something for which Otto Preminger had a particular penchant, and Angel Face and the equally brilliant Where The Sidewalk Ends are his best films, and among the great dark gems of Hollywood.

The Killing (1956) Stanley Kubrick

On Wednesday, April 2nd, Nights of Noir returns to Mother's Velvet Lounge when we present Stanley Kubrick's stunning sophomore offering, 1956's The Killing, starring Sterling Hayden, Marie Windsor, Elisha Cook Jr. and Vince Edwards.

Kubrick is generally counted today among the most important, influential and innovative directors in the history of cinema, but nearly a decade before he redefined the medium with Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and A Clockwork Orange, he was cutting his teeth on good old fashioned hard-boiled crime dramas, beginning with Killer's Kiss (1955) and it's higher profile follow-up, The Killing. With this film we really begin to see Kubrick's visual style begin to emerge through his inventive use of wide-angle lenses and blown out, diffuse light sources contrasting with bottomless pits of black. Apart from representing the emergence of the genius' vision, The Killing is also notable for being the one and only collaboration any film maker ever shared with the great crime novelist, Jim Thompson (The Grifters, After Dark My Sweet, The Getaway).

The story, told in a no-nonsense, police blotter style, revolves around a daring heist attempt at a racetrack, and introduces us to a cast of memorable down-and-outs, hoods and even a philosophical Russian wrestler cum chess champion. At the center of the action is Johnny Clay (Sterling Hayden) an ex-con with a brilliant plan and some dubious partners. Among them is George Peatty (Elisha Cook Jr.) a meek race-track cashier, cuckolded by his wife, Sherry (Marie Windsor – unforgettable as a first class man-eater) and the two of them shine as one of cinema's most entertainingly ill-matched couples. When she catches wind of her husband's new career in crime, Sherry hatches a little scheme herself in cahoots with her virile boyfriend, Val Cannon, played by Vince Edwards, who would go on to gain enormous popularity in the 60's as TV's Ben Casey.

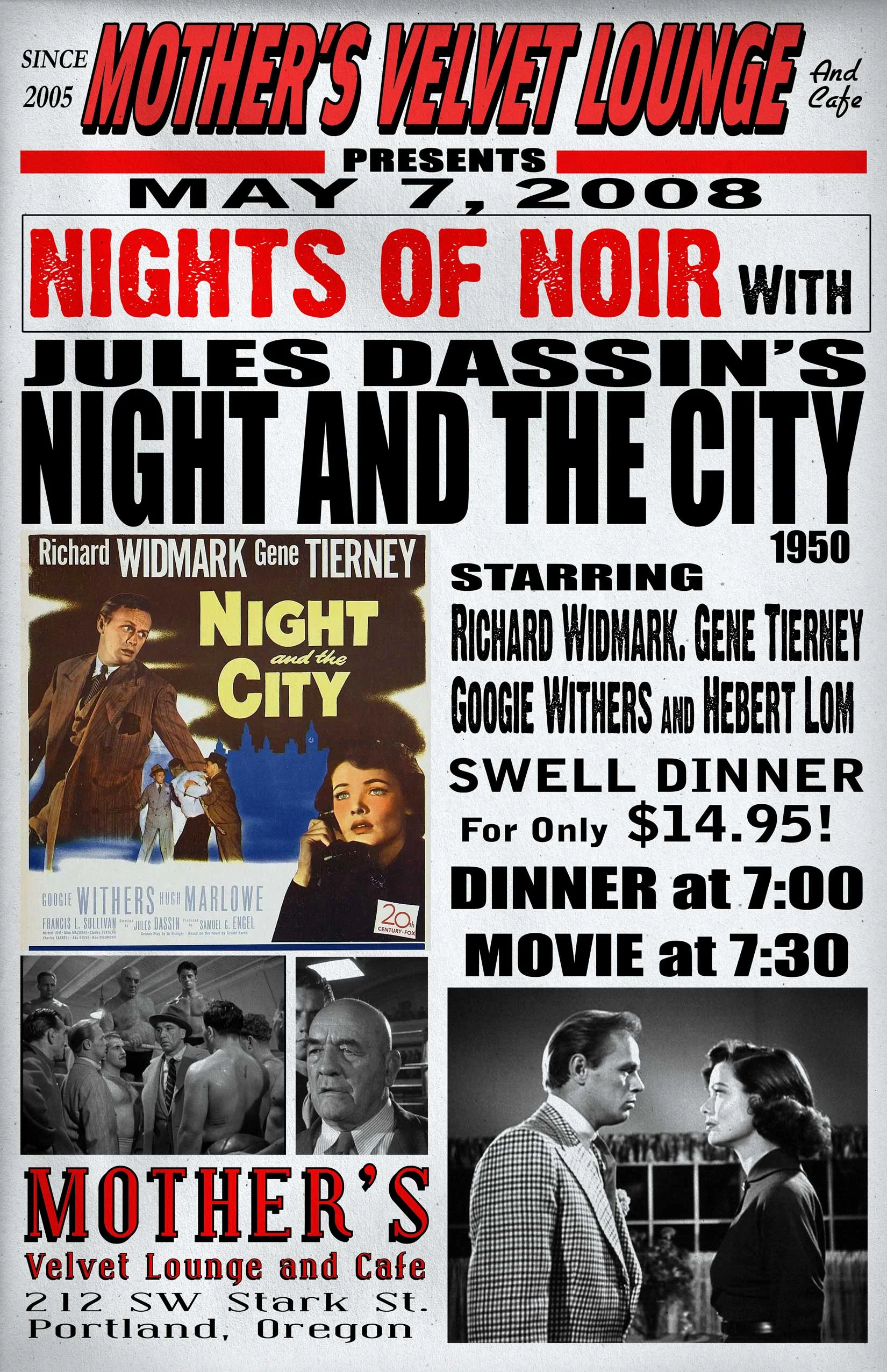

On October 8th, following a summer hiatus, Nights Of Noir returns to Mother’s Velvet Lounge when we present Tay Garnett’s classic 1946 adaptation of James M. Cain’s classic best seller, The Postman Always Rings Twice starring John Garfield and Lana Turner.

While many of you might be familiar with the Bob Rafelson’s 1980 remake starring Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lang, you are in for a real treat with the original adaptation which, for its time, was significantly more taboo breaking and revolutionary. The film does a remarkable job of negotiating the minefield of 1946 decency codes without ever compromising the illicit passions that drove Cain’s 1936 novel. The story had been Cain’s first foray into a murder story catalyzed by the unbridled sexual chemistry between two central characters. Like his Double Indemnity we are sympathetic to the misguided lovers because the emotional forces that pull them together are so vividly portrayed, yet we are afforded enough distance to foresee the disaster that awaits.

In Garnett’s film, Frank Chambers is a likeable everyman, who earns our sympathy early on thanks to an earnest and entirely believable performance by the great John Garfield, who’s acting style strikes one as distinctly contemporary when compared to most Hollywood actors of the day. And it doesn’t hurt one bit that Lana Turner’s tempting turn as Cora Smith makes a pretty strong argument for misplacing one’s moral compass. The chemistry between these two is explosive, and in 1946 their open-mouthed kiss was scandalous.

November 5th was the day following the 2008 presidential election, and one might recall the social atmosphere during that time when there was considerable murmuring of "only a heartbeat away" with regard to the Republican vice presidential candidate. The Manchurian Candidate came up a lot in conversation at the time, and it seemed too prescient a subject to ignore. I recall that most of our audience were breathing a collective sigh of relief on the day following the election and were happy to view the film more as a cautionary fable than a prophetic one. However, there was at least one viewer who was very unhappy with the previous day's tally, and likely viewed the film as poignant in an entirely different way.

Let’s face it. At this moment its nigh-on impossible for any of us to predict what our collective mood is going to be on November 5th, 2008, the day following what is possibly the most important Presidential election of our time. Personally, I’m putting my money on a jubilant and celebratory spirit, and the desire to sit back with a fine meal and to watch with relief, John Frankenheimer’s classic cautionary tale of hijacked democracy and mind control, 1962’s The Manchurian Candidate, starring Frank Sinatra, Laurence Harvey and Angela Lansbury.

Yes I know, The Manchurian Candidate isn’t exactly what we regard today as “Film Noir”. Its backdrop isn’t the gritty, intimate world of small time hoods, innocent bystanders, femmes fatale, or sexually motivated homicides. But what must be remembered is that when this adaptation of Richard Condon’s (Winter Kills, Prizzi’s Honor) novel was produced, there really was no such genre as “Political Thriller”, and Hollywood tended to prefer discussing political issues more metaphorically (take High Noon or Invasion of The Body Snatchers for instance). The atomic age brought with it a new social paranoia, and as a result Hollywood was emboldened enough in the early 60’s to address some of those fears head on. The idea that a treacherous plot to undermine American democracy from within the highest levels of political power had seemed like the stuff of complete fantasy until a deranged Senator from Wisconsin managed to generate such hysteria that even the President was powerless to stop him. And sure enough, when another President was gunned down in Dallas, this film felt less like an imaginative confection than prophecy. Indeed, The Manchurian Candidate was pulled from distribution for more than a decade following the Kennedy assassination, so discomforting as it was.

But, despite representing the birth of a new genre, Frankenheimer’s film drew heavily from many of the conventions of Film Noir, in both its narrative arc and visual style, so I don’t think it too much of a stretch to offer it as part of our series.

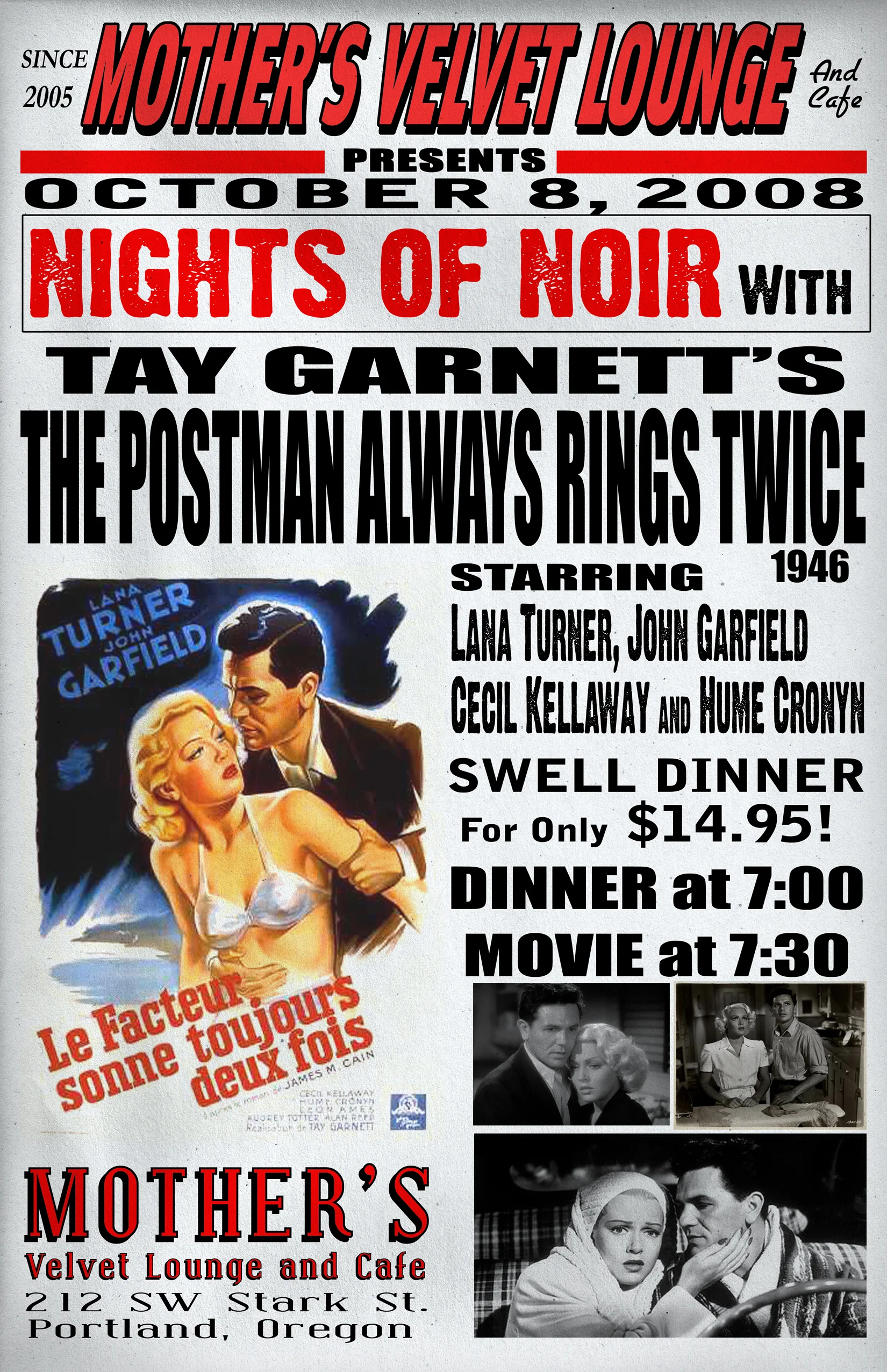

Sunset Blvd. (1950) Billy Wilder

First, I need to apologize for the shorter notice than usual. I usually like to give a week’s notice on these screenings, but November evaporated before I knew it.

On Wednesday December 3rd, Mother’s Velvet Lounge is happy to present Billy Wilder’s 1950 classic drama, Sunset Blvd. starring Gloria Swanson, William Holden and Erich von Stroheim.

Though one can debate as to whether or not Sunset Blvd. can really be categorized as Film Noir, what is not debatable is that it easily ranks among the top 10 or 15 works of American cinema. Though not the first time Hollywood looked inward to unveil some poignant truths about humanity at large, never had it been done with so keen and critical an eye and such a dark sensibility.

Silent film goddess, Gloria Swanson returned to the screen following an absence of nearly a decade to portray the fictitious silent film goddess, Norma Desmond; a fount of some of cinema’s most memorable lines (“I am big! It’s the pictures that got small.” and “We didn’t need dialog! We had faces”). As tenacious as she is tragic, Norma clings to memory of her long faded celebrity, refusing to acknowledge that her time has passed. Into her hermetically fossilized world stumbles (quite by accident) Joe Gillis (William Holden) a down-on-his-luck screen writer who, though initially repulsed by Norma’s overbearing drama queen shtick, is eventually drawn into her deluded reality. The whole bizarre mélange is scrupulously watched over by Norma’s humorless Teutonic manservant, Max (Erich von Stroheim) whose haunting visage suggests an even darker reality in the Desmond household.

Panic In The Streets (1950) Elia Kazan

On January 14th, Nights Of Noir returns to Mother’s Velvet Lounge when we present Elia Kazan’s classic 1950 urban thriller, Panic In The Streets, Starring Richard Widmark, Jack Palance, in his first film role, and the great Zero Mostel.

Richard Widmark plays Lt. Cmdr. Clint Reed M.D., a Public Health Service officer in New Orleans who, when called in to the morgue to examine a homicide, discovers that an outbreak of pneumonic plague is imminent unless he can track down everyone who has come into contact with the victim…including his murderers. Jack Palance debuts as Blackie, a homicidal hood who has no idea how big a threat to the public safety he truly is. He’s accompanied throughout by his simpering sidekick, Raymond, beautifully played by Zero Mostel, also in one of his first film roles.

This marks Kazan’s second foray into the genre of crime drama’s that were a Hollywood mainstay in the post-war years (the first being Boomerang) though, while it certainly possesses the key ingredients of Film Noir, Kazan’s passion for social realism which marked his best known films (A Streetcar Named Desire, On The Waterfront) truly sets it apart. The film was shot on location in New Orleans, and uses a lot of local color in an almost documentary fashion, as non professional actors offer extremely genuine glimpses into the underclass of a big city. Kazan is equally fascinated by his protagonist’s home-life, and the simple financial troubles he and his wife (played by Barbara Bel Geddes) share, are given nearly equal weight to the potential of a city-wide pandemic.

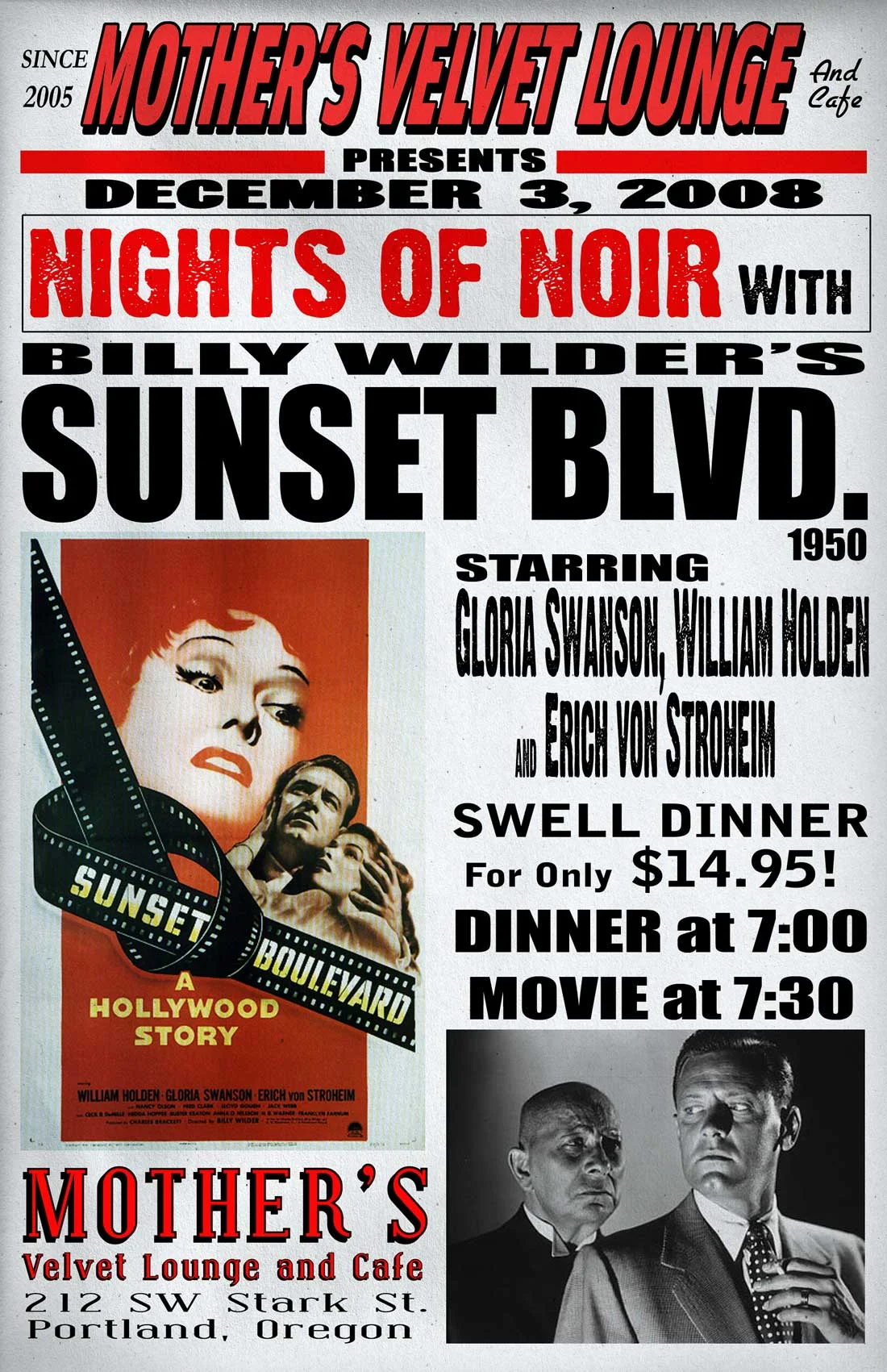

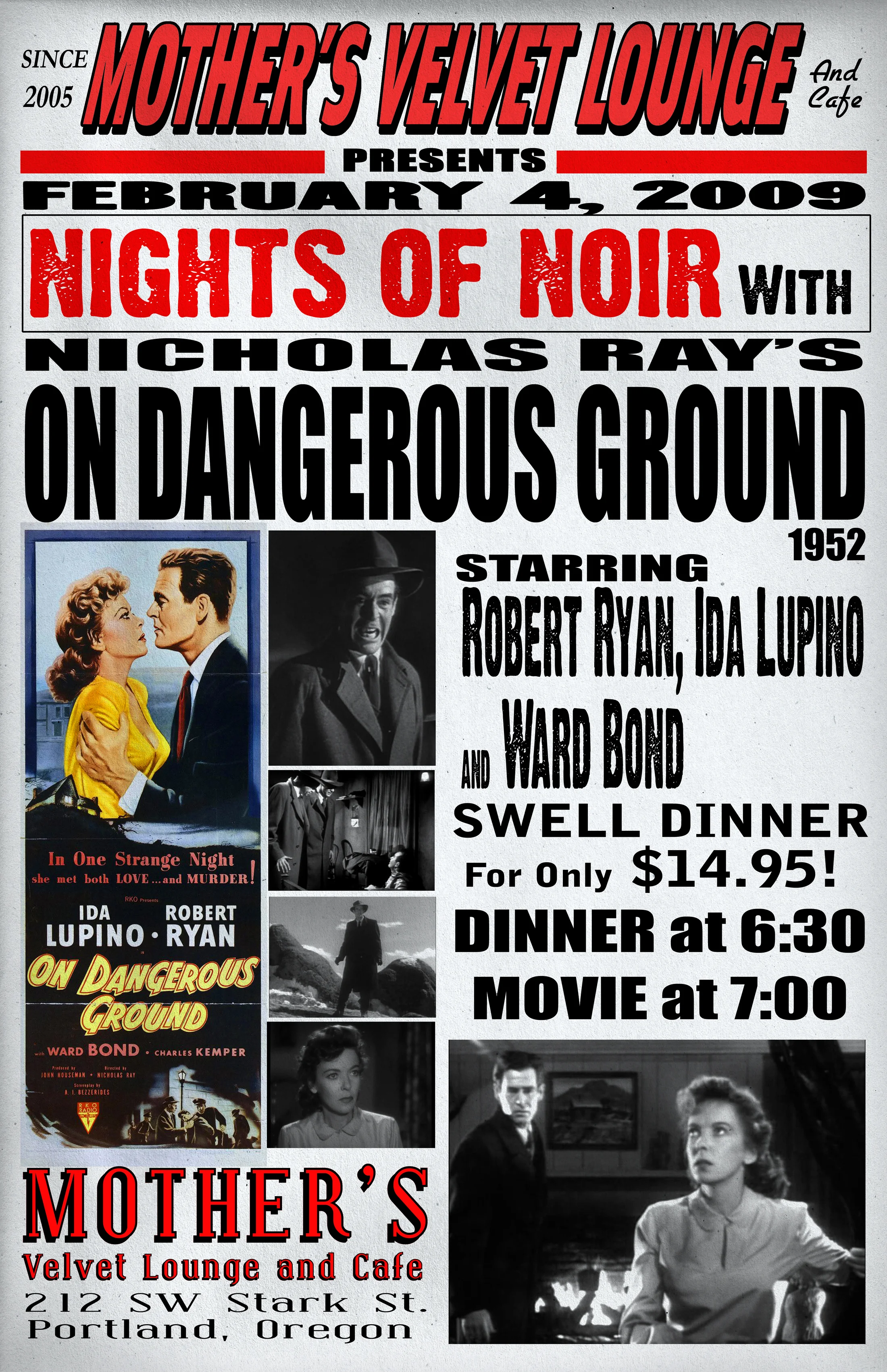

On Dangerous Ground (1952) Nicholas Ray

On Wednesday, February 4th, please join us at Mother's Velvet Lounge when we present Nicholas Ray’s classic tale of violence and redemption; 1952’s On Dangerous Ground, starring Robert Ryan, Ida Lupino, and Ward Bond.

Robert Ryan, in one of his signature roles that blurs the lines between heroism and villainy, plays Detective Jim Wilson, a cop who has dealt with the dregs of society so long that he has lost the thread of his own humanity. His chief decides to get rid of him by sending him on assignment to investigate the murder of a young girl in a small rural community in the mountains. His search for the murderer brings him to the remote home of the principle suspect’s blind sister, Mary Malden (Ida Lupino), to whom he finds himself strangely drawn…

On Dangerous Ground is one of Nicholas Ray’s lesser known films, but I would argue among his most memorable. It explores themes that he came back to quite often including social alienation (Rebel Without a Cause, The Lusty Men) and masculine rage (In a Lonely Place), and despite it’s hard-boiled first act, it is probably one of the most humanist of post-war Hollywood crime films. Apart from a brilliantly tense performance from Robert Ryan, the film is notable for its documentary style hand-held cinematography in the urban sequences, and for a thrilling score by the great Bernard Herrmann (Citizen Kane, Psycho) which serves as something of a fore-runner to his soundtrack for North By Northwest.

The Naked Kiss (1964) Samuel Fuller

On March 4th, Nights of Noir returns to Mother’s Velvet Lounge when we present Samuel Fuller’s bizarre and daring 1964 psycho-sexual thriller, The Naked Kiss staring Constance Towers.

From frame-one, we know that we aren’t watching any ordinary crime thriller when bald headed prostitute, Kelly (Constance Towers) nearly beats her pimp to death with her handbag. The attack feels almost as though it’s directed as much towards the audience as the object of her hatred. From there, Fuller takes us on a tour of a life rarely glimpsed in Hollywood features, and as the tale unfolds, his uncompromising perspective on society and the lies it feeds itself are drawn in delightfully trashy detail.

This really represents the end (or at least the beginning of a very long sabbatical) of Fuller’s relationship with the Hollywood movie industry, and given the dicey subject matter (wouldn’t want to give it away) it feels like a bit of a goodbye kiss. Like much of his most memorable work, his protagonists are not only the inhabitants of society’s periphery, but as such, he paints them as its moral center. Fuller blends his assault on the mythos of small town America with unapologetic pulp trappings and even includes a nearly surreal musical number that will have you either in hysterics or shaking your head with disbelief.

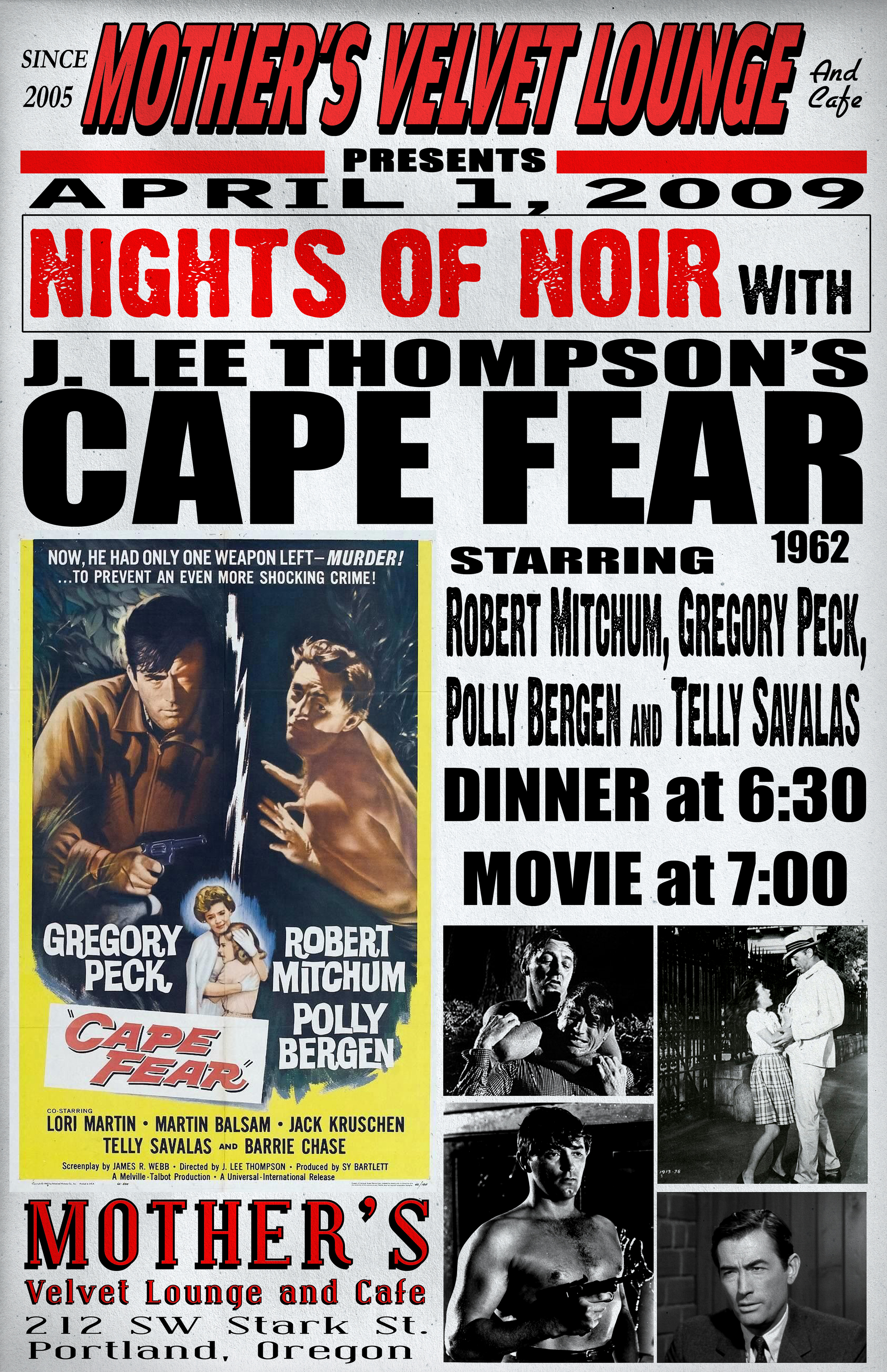

Cape Fear (1962) J. Lee Thompson

On April 1st, Nights of Noir returns to Mother’s Velvet Lounge when we present J. Lee Thompson’s riveting 1962 thriller, Cape Fear, starring Robert Mitchum, Gregory Peck, Polly Bergen, Martin Balsam and Telly Savalas.

Made during a period when a number of Hollywood directors were drawing inspiration from the Hitchcockian model of suspense, Cape Fear stands out as one of the few that can actually stand head to head with much of the master’s work. British director J. Lee Thompson, a seasoned director of British thrillers and war films had just come off of The Guns Of Navarone (which arguably set the tone for adventure cinema for the next 20 years), and his deft handling of both suspense and action reached its zenith with this, his strongest film.

Sam Bowden (Gregory Peck) is a small town lawyer and family man whose life is turned upside down when Max Cady (Robert Mitchum), insinuates himself into his tranquil life. Having just completed an eight year prison sentence for a brutal rape, for which Sam’s testimony against him had been instrumental, Max begins by needling and provoking Sam, while remaining well within the law. As Max’s threatening presence begins to tear at the fabric of Sam’s family, the two men engage in an explosive battle of wills that draws them towards a terrifying and dramatic conclusion.

But the real star of the show is Mitchum, who delivers what I believe to be the most powerful performance of his career. His Max is a good ol’ boy, with a jovial and familiar air that effectively hides a wrathful psychopath, and unlike DeNiro’s interpretation of the character in Martin Scorsese’s 1991 remake (which I’ve always seen as a sort of fusion of Max and Mitchum’s other great screen villain, Harry Powell in Charles Laughton’s The Night Of The Hunter – 1955), you can readily understand how his seductive façade could draw his victims in.

On May 6th, Nights of Noir returns to Mother’s Velvet Lounge when we present Robert Aldrich’s classic 1962 Battle of the Battleaxes, What Ever Happened To Baby Jane, starring Bette Davis, Joan Crawford and Victor Buono.

While perhaps stretching the common definition of Film Noir a bit, the feeling here was that this dark, and occasionally comic masterpiece serves as a fitting follow up to Sunset Blvd. (which we screened back in December). With these two films, Hollywood caught up with the vision of itself so vividly described By Nathanial West in his 1939 novel The Day Of The Locust, as a crumbling façade of cruel illusion. The fate of the has-been is portrayed as a psychologically torturous one, and the curse of having once “been someone” is often the path to madness.

Bette Davis (who received her 11th Oscar nomination for this film) plays Jane Hudson, an aging and long forgotten child actress whose state of arrested development tends to get in the way of taking particularly good care of her wheelchair bound sister, Blanche (Joan Crawford), who herself had once been a famous beauty and film star. The tensions between the two are fueled by the possibility that Jane may have had a role in her sister’s disability. The responsibility and guilt, along with a life squandered on her caretaker role has brought Jane to the edge of sanity, and when she begins to foster the idea of a comeback, her psychological collapse seems imminent…

At the time of its release, much was made of this, the first and only pairing of Davis and Crawford who, a quarter of a century earlier, were the reigning queens of Hollywood and had famously shared an intense dislike for one another, fueled by bitter jealousy. While such casting could easily have resulted in a dysfunctional disaster for a film production, both women were unequivocally consummate professionals and if anything, their rivalry prompted them to render forth the performances of their careers.

Robert Aldrich (Whose 1955 classic Kiss Me Deadly, we screened back in December of ’07) possesses the unusual distinction of having specialized in two distinctly different types of film. For all of the testosterone fueled tales of survival and action he has done (The Dirty Dozen, The Flight Of The Phoenix, Emperor Of The North Pole and The Longest Yard), there are films like “Whatever Happened to Baby Jane” that pit two mature women against each other, often played out in a show biz milieu (Hush, Hush Sweet Charlotte and The Killing Of Sister George).

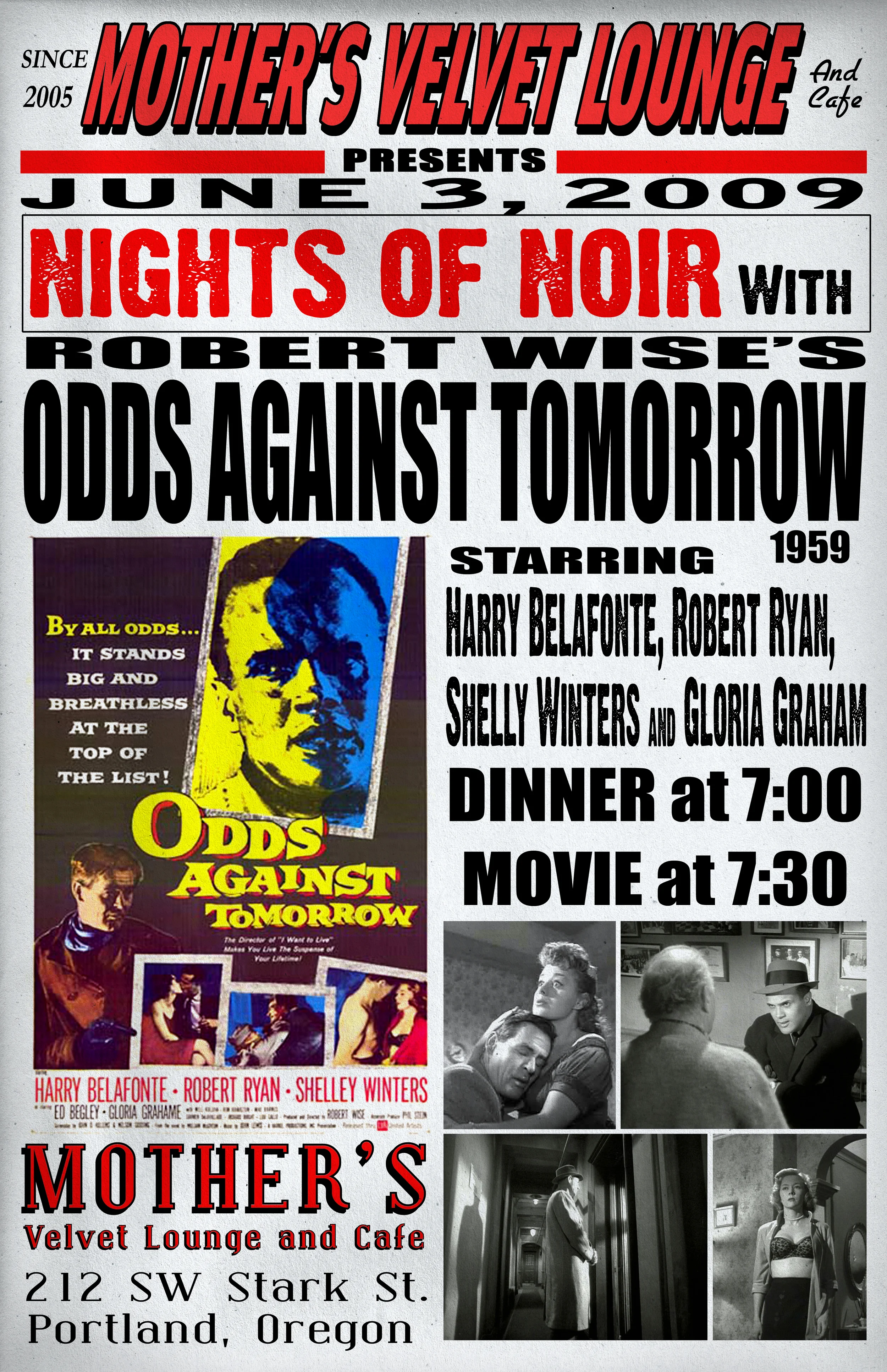

Odds Against Tomorrow (1959) Robert Wise

On June 3rd, Nights of Noir returns to Mother’s Velvet Lounge when we present Robert Wise’s hard-hitting and racially charged 1959 crime thriller, Odds Against Tomorrow, starring Harry Belafonte, Robert Ryan, Shelly Winters, Ed Begley, and Gloria Graham.

Though racism, had been tackled by Hollywood in a small number of films during the 50’s (Joseph Mankiewicz’s 1950 No Way Out which pitted Richard Widmark’s white supremacist thug against Sidney Poitier’s dedicated physician, is one of the better examples), it was certainly rare for a genre film to use racial tension as a dominant purveyor of dramatic tension. What stands alone as a handsomely realized and atmospheric heist caper in the tradition of The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston - 1950) and The Killing (Stanley Kubrick – 1956), is given added sociological weight when the explosive mixture of a self-loathing Southern racist (Ryan) and a down-on-his-luck African American gambler (Belafonte) are thrown together by a disillusioned ex-cop (Begley) to help execute his big bank job. What is particularly impressive for a film made at the dawning of the civil-rights movement, scripted by a black-listed Marxist writer (Abraham Polonsky), is that it doesn’t simply portray the black man as an innocent, nor the racist as a two-dimensional monster (though he is damn scary), but instead imbues both characters with remarkable depth.

Robert Wise is easily one of the most versatile and successful of Hollywood’s directors of the 50s and 60s. Having cut his teeth as one of the two editors on Citizen Kane (Mark Robson being the other), and even taking over for Orson Welles when the studio demanded additional shooting on The Magnificent Ambersons, he would go on to direct low-budget horror films for producer Val Lewton at RKO. His remarkable range can be seen in some of the finest examples of films within their respective genres, including prize-fight dramas (The Set-Up – also starring Robert Ryan, in possibly the best performance of his career), war films (Run Silent, Run Deep and The Sand Pebbles) science fiction (The Day The Earth Stood Still and The Andromeda Strain), Horror (The Body Snatcher and The Haunting) and even musicals (West Side Story and The Sound Of Music). It’s difficult to think of a Hollywood director of the “pre-auteur” generation possessed of so impressive a batting average. Odds Against Tomorrow added a brilliant and memorable example of Film Noir to his already impressive CV.